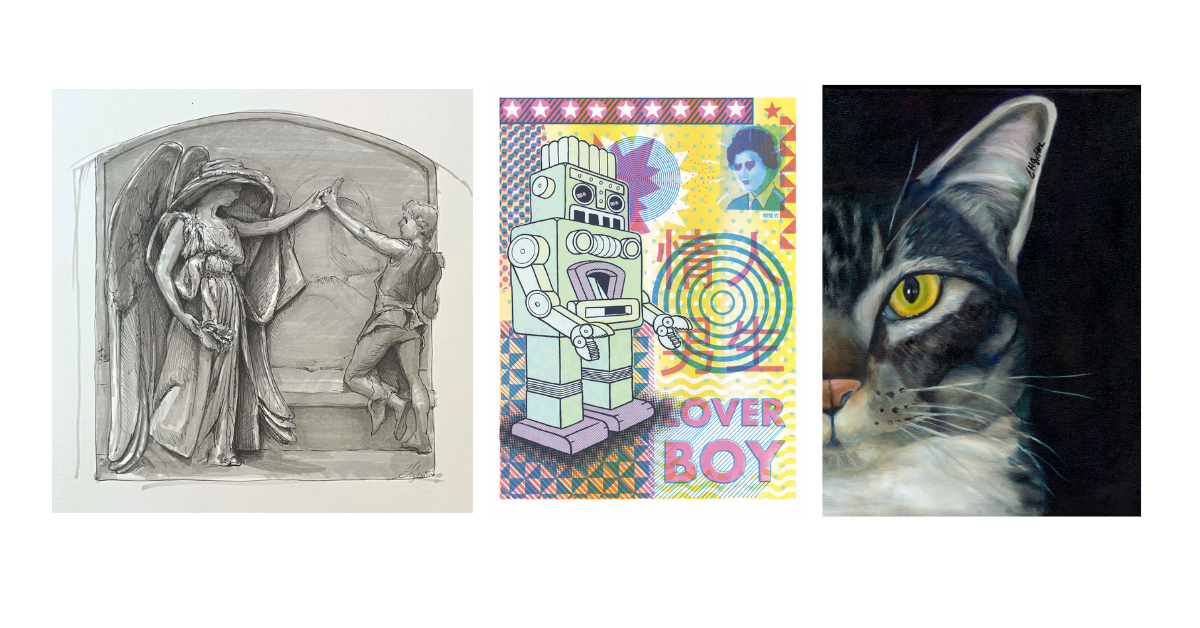

Photos courtesy of Emily Griffith Byrd, Chad Tolley and Andrew Swift.

Emily Griffith Byrd

is a recent transplant to Augusta who is known for her expressive pet portraits.

How did you become a professional pet portraitist?

Originally, I had worked in the entertainment industry in Hollywood and then was working at a TV station in Denver, but I wasn’t happy. So, I did The Artist Way by Julia Cameron, and a friend of mine suggested that I start painting. Instinctually, I did a painting of my dog. Then I did another one for a neighbor and they started selling. After moving to Atlanta, I started training with a fine art artist in oil paints and focusing on painting animals. I found the online class of pet portraiture from the London Art College and learned more intense detail of painting pets through the course. But the instructor told me from the beginning not to change my style — she really loved my style of painting.

Describe your creative process.

My tag is ‘painting pets with personality.’ I capture the personality by focusing firstly on the eyes, nose and mouths. For some dogs, like the Golden Retriever, their fur is part of their personality. Or for the bulldogs, it’s their wrinkles and their mouths — how they slobber — or for poodles, it’s their curls. After all these years, I am very familiar with the typical breed features and personalities so I can easily pull out those elements while I paint.

How did you get noticed by Sonny Seiler and his famous University of Georgia bulldogs?

I had done a painting of a bulldog and a friend mentioned that I should try to paint Uga. I sent a notecard of my bulldog painting to Mr. Seiler saying I would really be interested in painting Uga. He immediately responded! I met him in person (we quickly hit it off since my dad was a larger-than-life personality and lawyer like Mr. Seiler) and he allowed me to take pictures of VII, VIII and IX. The Uga paintings are some of my favorites due to all their expressive wrinkles, the jowls and drool.

What are some of the reasons you chose pets as your imagery?

The pet portraits seem to be especially healing for owners who have lost their pets. I’ve gotten notes from clients saying the process has been healing for them, and even been told that husbands start crying when they see the final painting. I really enjoy having a gift that helps others heal from pain or trauma or hard circumstances. My husband and I support a lot of nonprofits. I often offer paintings as a way for these groups to raise money for important causes whether it be foster care, addiction awareness or safe homes. There is something about helping people through the medium of my art that keeps me deeply connected and grounded to the positivity of life.

Chad Tolley

teaches printmaking and drawing at Augusta University and exhibits across the United States.

Could you explain printmaking and what drew you to the art?

Printmaking includes paper making, bookmaking, letterpress or relief, block letters, woodcut, etching, engraving, lithography, screen printing … there are a lot of different areas that are considered printmaking. It is a three-year Masters program and it’s very technical. I have an engineer’s mind. That is what draws me to printmaking, the technical process — the problem-solving and critical thinking — behind the art. You must be able to think ahead, visualizing multiple steps in advance and you must understand the technical aspects of the chemistry, layering, stacking … those kinds of things.

Talk about the playful imagery in your prints and how they relate to you.

There was pressure in grad school to make really serious art, but I didn’t enjoy making serious art or sticking with a particularly rigid thesis. So, I just got back to the fun, playful approach to art. I like to play. I tell students that it is okay to make art that is not super deep. It’s okay for color, shape and line to be your concept. It can be just about good design, good balance and harmony.

Are there narratives underneath your art?

Some of my work is about memory. I work intuitively, so my imagery begins with colors and textures and mostly whatever I am thinking about at the moment. For some works I have drawn from old cartoon styles. But I am not communicating a storyline; there is definite ambiguity in my work. I like exploring fragmented ideas, bouncing around from one idea to the next. Sometimes that becomes problematic because I don’t always know what I am going to do next, and the works don’t always fit together. But, I do like to create a little tension, there’s always a little subversion in the works. Like the cartoons that are juxtaposed to something perhaps serious, there’s always a kind of undercutting there.

Tell us about the relationship of printmaking to students today.

Printmaking is the progenitor of graphic design. Originally, graphic design was all done by hand. When I teach printmaking, I help students to think in layers, building colors and images while remaining mindful about the stages. It can be hard for students because it is so technical. At first, they don’t like the work since the process is labor-intensive. So, I will give them one way, for instance, to use only three colors (cyan, magenta and yellow) and repeat imagery to create a tessellation [duplication of tiles]. I am trying to show students how to get ‘the most juice out of one squeeze.’ After the first couple of assignments, they start to understand the appeal.

Andrew Swift

is a medical illustrator whose detailed drawings will be on exhibit for the first time at CANDL Fine Art.

Describe your interest in medical illustration.

I’ve been a medical illustrator for 25 years. I went to college and majored in biology and then I taught school for a year at Jekyll Island at the 4-H Center. Afterward, I landed a job in the Peace Corps. It was there that I learned the business of taking an assignment, dealing with clients, delivery/production issues — the mechanics of working as an illustrator. When people want proof that I’m a nerd, I show them my medical illustration encyclopedias that I read from cover to cover for personal inspiration. They are beautifully written and exquisitely illustrative, exposing stippling and zip-a-tone [a material used in old school illustrations]. One of my favorite illustrators would do his own electron micrcoscopy — he was an educator and an illustrator producing profoundly comprehensive volumes.

Will the world need medical illustrators in the future?

Medical illustrators create visual narratives through stylizing, exaggerating or modifying things to tell a story. We are working with AI, but AI is not there yet. I can’t tell AI to give me a lymphocyte traveling through a lymph node, picking up an antigen, moving from [receptors]etc., because it’s gonna make a bunch of stuff that’s gonna look right but it’s not. Someone has to go back and fix it. In fact, we created a Venus-anatomy viewer and asked AI to write descriptions of each vein. It did a pretty good job, about eighty percent accurate, but it would say this vein drains into that vein. But it doesn’t. It still needs someone who knows the accurate functions. So, I think for now, medical illustrators are safe.

How does your artwork intersect with the medical application?

I’ve always drawn. I think I have an affinity for it based on the way I see form in the natural world. A lot of that comes down to morphology, or how shape defines an organism. Today, I am always drawing, scribbling on napkins or scraps of paper. Quick studies. I love drawing birds and maps. There is a map of the West Indies and Africa in the exhibit. In the same way, the anatomy of the body is a map. I did a drawing of the brachial plexus [a network of nerves in the shoulder], so I made this medical representation of the nerve system with QR codes so people can scan the code and then see each part’s function. The next iteration of this model will include LEDs lighting up the pathways of how the nerves communicate in the body.

Tell us about storytelling in terms of medical illustration.

An illustrator’s job is to communicate through the drawing what is important. Let’s say the spleen is most important, then the spleen gets all the color, the contrast, the detail. Everything around it is less colorful, more desaturated, vignetted … less detailed. That tells the viewer that the story is the spleen. That is our job. We drive the visual narrative by ordering the image. We use a standardized skillset, but the most important thing is that the intended audience understands the visual narrative. You can go as deep or as surface as is intended. So, it’s really a matter of understanding the science of something and then rendering that as a digestible application to a specific audience.

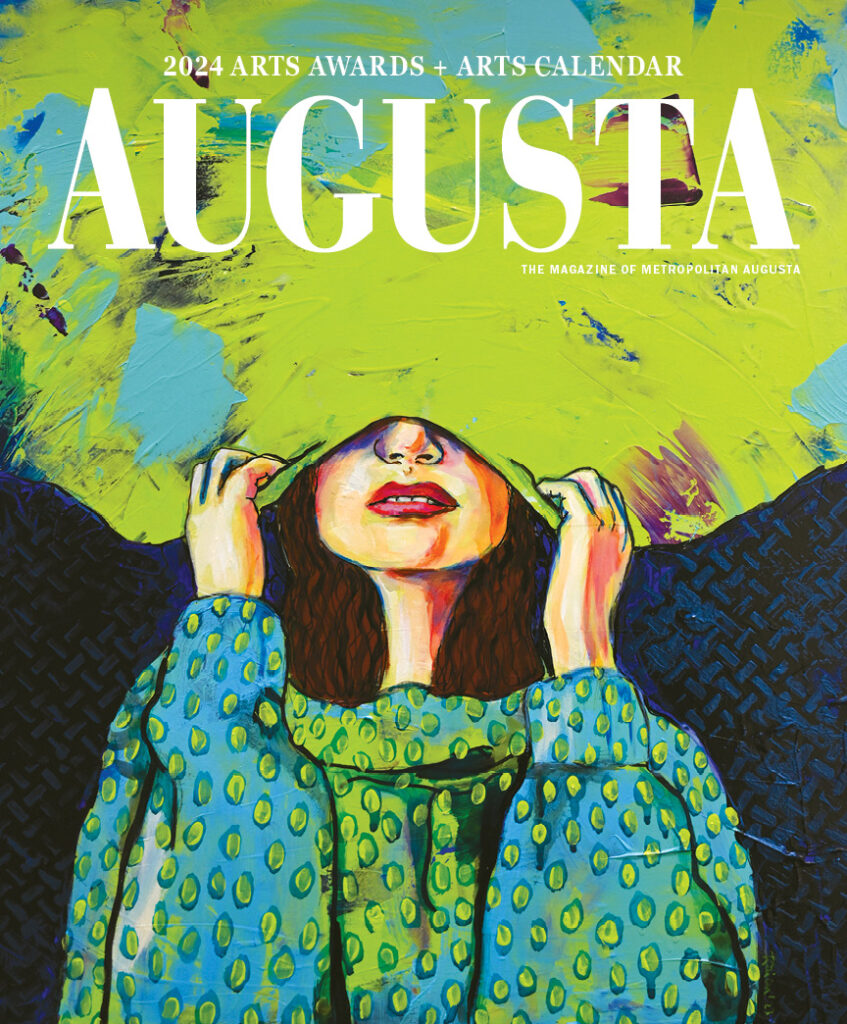

Seen in the August/September 2024 issue of Augusta magazine.